- Home

- Hamish Ross

Paddy Mayne

Paddy Mayne Read online

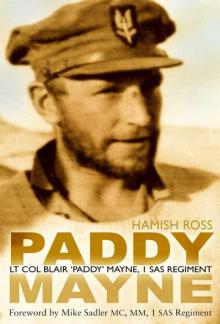

PADDY MAYNE

LT COL BLAIR ‘PADDY’ MAYNE, 1 SAS REGIMENT

HAMISH ROSS

First published in 2003

This edition first published in 2004

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

©Hamish Ross, 2003, 2011

The right of Hamish Ross, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6965 2

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6966 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Foreword by Mike Sadler, MC, MM, 1 SAS

Preface by Fiona Ferguson, niece of Lt Col Mayne

Acknowledgements

Part I

1 The Legend

2 Ireland 1915–1940

Part II

3 11th (Scottish) Commando

4 The Desert Raiders

5 Special Raiding Squadron

6 Fair Wind for France

7 Later Operations

Part III

8 Antarctic Interlude

9 My Usual Quiet Life

Part IV

10 Ashes of Soldiers

11 Growth of a Unit

Glossary

Notes

Bibliography

FOREWORD

Mike Sadler, MC, MM, 1 SAS Regiment

It is good to be able to welcome a new assessment of Blair Mayne – Paddy, to all who knew him in the wartime SAS. There were certainly a number of fellow Irishmen in the regiment at that time, but there was never any doubt as to whom one meant when referring to Paddy. Good also to see a new appraisal at the present juncture when the band of those who got to know him in the war is rapidly diminishing. Furthermore, through his meticulous research the author has turned up much new information, which has become available since the last time anything was published about Paddy and contributes to casting new light upon his outstanding abilities as an unorthodox soldier and on his unusual personality.

Although much has been written in the past about Paddy’s exploits, some of it has seemed misleading and even rather derogatory. This has been due, in part, to its having been based on hearsay long after the event, and sometimes to the writers’ inclination to exaggerate a situation for dramatic effect. The present author’s researches should go far to provide a more balanced picture of a most remarkable man, and should provide rewarding study for anyone interested in the past history of irregular warfare.

I was fortunate to see quite a lot of Paddy, both in operational and social situations during the war. I first met him in the dusty desert outside Jalo, behind enemy lines in Libya. I was navigator in the LRDG patrol which was to take him and his small SAS team to the vicinity of an enemy airfield at Wadi Tamet, some 350 miles yet further to the west, where he would carry out the first successful raid of the many he was to undertake against enemy airfields. Thereafter, having myself transferred to the SAS, I saw much of him in the desert, accompanied him when he parachuted into occupied France, celebrated with him in Paris (perhaps rather too liberally) following its relief, joined him on visits to his home in Ireland, and saw something of him in the Antarctic on his unfortunately curtailed visit to the south at the end of the war.

From the earliest days, it was obvious to all that Paddy was a brilliant and determined operator in the field. What was less obvious – at least to the rank and file such as myself – until the capture of David Stirling led to Paddy’s elevation to command of the regiment, was that he had also developed a considerable talent for the arts of leadership, planning and staff work. The extent to which this has been revealed in the course of the author’s researches has been of particular interest to me and no doubt to all who have followed the many and varied interpretations of Paddy’s career and character. However, his abilities as an administrator notwithstanding, there is no doubt that he could hardly wait to get back to operations in the field, which is where his greatest talents lay.

Although he was a very complex character, and could certainly be unpredictable at times, he was a great person to be with in almost any circumstances. A quiet man who hardly ever raised his voice, he got the results he wanted by his large (in every way) presence and by example. Everyone was very much aware that he would never expect anyone to do anything, or to take any risk, that he was not prepared to undertake himself; and this certainly contributed to his success as an outstanding leader of soldiers in the field of unconventional warfare.

PREFACE

Fiona Ferguson, niece of Lt Col Mayne

Hamish first approached me two and a half years ago with the idea of writing an article about my uncle Blair. I was at first very hesitant – was this going to be a rehash of the old stories, only even more embellished? Even as a young girl I was aware that ‘everybody’ knew Blair personally, and, once my relationship was known, I would have to listen to an even better version of a story I had heard many times before. The pubs in Newtownards must have made a fortune from the number of people in them when Blair was there who had witnessed these deeds in person. I also didn’t see how I could help. I was only ten when Blair died – my father had given the war diary to the SAS and all I had were the scrapbooks of newspaper cuttings kept by my Aunt Barbara, letters and other documents kept by various members of the family, especially my father and Aunt Francie, plus some of Blair’s own papers.

However, Hamish had been given my name and address by Jimmy Storie, whom I had met at the unveiling of the statue of Blair in Newtownards and on a couple of occasions since with his lovely wife Morag. If Jimmy was prepared to talk to Hamish it would be churlish of me to refuse to help in any way I could. What I hadn’t realised was that among Francie’s papers, which came to me on her death, was a diary that Blair had kept in the Antarctic. Soon after he had read this I realised that Hamish was determined to get to the true man and was doing his utmost to talk to the few remaining people who really knew Blair – not those acquaintances who claimed friendship so as to bask in the reflected glory.

I knew my father would not react kindly to the idea of a new book, so I did not tell him until I was convinced that Hamish was after the truth – warts and all. Dad has now read the manuscript and is very impressed with the research Hamish has undertaken. No previous author has attempted to do anything similar – they have just reiterated the stories of armchair friends.

If anyone were to ask me which book they should read about ‘Col Paddy’, my unreserved answer would be, ‘the one by Hamish Ross’.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

What began as an idea for a journal article on Blair Mayne’s transition from Special Services leader to legal administrator developed into this book thanks to the range of the papers that his family kept. So I am therefore most grateful to Fiona and Norman Ferguson for giving me access on different occasions to the Mayne family papers, specially to Fiona for her patience in responding to my many queries, and for writing a Preface.

I am particularly indebted to the Secretary of the Special Air Service Regimental Association for giving me acces

s to what the Regimental Association refers to as ‘The Paddy Mayne Diary’, as well as to other files, and for enabling me to contact former members of 1 SAS Regiment. I should like to thank those contemporaries of Blair Mayne, who not only gave their time to my questions, but reviewed the written transcripts of their interviews, and, in many instances, over a prolonged period, were prepared to re-engage in discussion in the light of further documentation which emerged. I especially want to thank Mike Sadler for the input he gave over almost two years and for writing the Foreword to the book.

For permission to use copyright material I should like to thank Margery Badger, Anne Holmes, George Franks, Elizabeth Humphryes, James O’Kane, Registrar Queen’s University Belfast, Stewarts Solicitors, Newtownards, Eoin McGonigal, Senior Counsel, Dublin, Professor Graham Lappin, Martin Vine, Archivist, British Antarctic Survey, Lady Jean Fforde and Sir Thomas Macpherson.

Lines from ‘Under Ben Bulben’ by W.B. Yeats are taken from the Everyman’s Library anthology, Yeats Poems, 1995, and are reprinted by kind permission of the publisher. The extract from Once There Was A War by John Steinbeck, Penguin, 1977, © John Steinbeck, is reprinted by kind permission of the publisher. The stanza from Sorley MacLean’s ‘Going Westwards’ appears in From Wood to Ridge, 1999, published by Carcanet Press and is reprinted by kind permission of the publisher. The extract from The Naked and The Dead by Norman Mailer is reprinted by kind permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, © Norman Mailer, 1949. Lines from ‘Digging’ from Death of A Naturalist by Seamus Heaney are taken from the anthology Opened Ground: Poems 1966–1996, 1998, and are reprinted by kind permission of the publisher, Faber & Faber Ltd.

I am grateful to a number of people for specific help. From the University of Glasgow, Bill Buckingham, Department of Modern History, Mike Shand, Department of Cartography, Cathair O’Dochartaigh, Department of Celtic, Willie McKechnie, Photographic Unit and James Steel, Department of French. I would like to thank Mark Creamer, Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Karen Robson, Senior Archivist, University of Southampton, staff at the Public Records Office, the staff of Whiteinch Library, Ian (Tanky) Smith, Jimmy Lappin, Ewan Ross, John Lewes, Eric Taylor, Heather Semple, Head of Library and Information Services, The Law Society of Northern Ireland, William Cumming, solicitor, Terence Nelson, Royal Ulster Rifles Association Museum and Clifford Manley, Vice Principal Regent House Grammar School.

I want to thank Stewart McClean of the Blair Mayne Association for his help and unfailing courtesy; and I would like to make particular mention of the excellent help of David Buxton. Walter Marshall, who has done so much to perpetuate a record to No. 11 Commando, has been most supportive, and Eileen Mander and Archivist Stuart Gough of the Isle of Arran Heritage Museum gave valuable assistance.

Finally, for meeting me when the book was nearing completion and for giving me his encouragement, I should like to thank Douglas Mayne.

PART I

I

THE LEGEND

Ransom Stoddard: You’re not going to use the story, Mr Scott? Maxwell Scott: This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

from the film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, directed by John Ford

An Irish solicitor, Blair Mayne – or Paddy Mayne as he was more widely known – became one of the most outstanding soldiers and leaders of the Second World War. He had been an international rugby player, who represented Ireland and played for the British Lions before the war; and after serving in a Commando and seeing action in Syria, he joined the new unit that David Stirling was establishing – the Special Air Service. The record of Mayne’s achievements in little over twelve months with the SAS in the North African Desert reads like fiction; yet it is factual and well recorded. The groups he led destroyed over one hundred enemy planes on the ground. These raids, with few exceptions, were carried out on foot and by stealth. Luck was an element in these successes, but the one common factor was Mayne’s ability to read the situation on the ground, anticipate how the enemy would react, and then attack. He was twenty-seven years of age when he won the DSO for the first time. Over the next three years, Mayne led the unit in Sicily and mainland Italy in a very different kind of warfare; then in France, behind enemy lines; and in Germany, where the unit was the spearhead of an armoured thrust. In each of these three campaigns, he added a further bar to the DSO, then received the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d’Honneur. At the end of the war, after a short period with an Antarctic Survey, Mayne returned to the law, becoming a senior official in the Law Society of Northern Ireland. In 1955, he died in a car accident at the age of forty.

Heroic military figures have long been the subject of public interest, not only because of their achievements, but for what motivates them. There is fascination with the heroic contempt for personal safety that defies common experience; and there is something of an aura of mystery about the hero, which often gives rise to legend. In Mayne’s case, the newspapers began the trend during the war: he was compared to Bulldog Drummond,1 the fictional hero of spy thrillers of the twenties and thirties; and he was also described as a famous pre-war international sporting figure, coolly strolling into an enemy officers’ mess and attacking its occupants, before moving on to the next job; and by the time he was decorated by the king with the third bar to the DSO, they had increased his height by four inches to six feet six. Decades later, first a radio series and then a television programme about Mayne made their contribution with hyperbole.

At the end of the war, though, the first personal accounts began to emerge from those who had served in the SAS. A maxim that has long been established in combat units is that comrades know those who are truly worthy of recognition. Two of Mayne’s colleagues wrote of their time in the SAS: Malcolm James Pleydell,2 its first medical officer, and Fraser McLuskey,3 its first padre. Both men wrote insightfully of Mayne, what manner of man he was, and of the respect and regard in which he was held by his men.

But soon after his death, however, misinformation about Mayne began to appear, first of all in books about others. Keyes somewhat pejoratively attributed to him the authorship of an operational report of a troop’s actions at a Commando raid in Syria,4 which in fact had been written and signed by another officer.5 Two years later, Cowles erroneously claimed that Mayne’s progression from the Commando to the SAS came about when he was rescued after some weeks under close arrest for having punched his superior officer.6 In reality, Mayne had left the unit the previous month.7

The first book about Mayne was written by Patrick Marrinan8 and appeared two years after the claim by Cowles. Marrinan approached his material very much in the tradition of a Boy’s Own account. He had read Cowles’ account of the early SAS and cited from it; and he simply accepted the fanciful tale of how Mayne came to join the SAS, and went on to create a scenario for it. To be fair to Marrinan, at the time he would not have had access to the war diaries which would have given evidence to refute the claim. But, on the other hand, Mayne was his subject (since Marrinan had been a barrister, Mayne was also in a sense his client) and he had read his letters, which, if he had cross-checked with published accounts about No. 11 Commando, at least would have made him question the unfounded claim. Instead, he consolidated a legend: the future leader of the SAS was brought into the light from prison to be offered the opportunity to prove himself and become its greatest warrior. Throughout, Marrinan treated Mayne as a larger-than-life character, personally motivated, whose actions happened to coincide in general with the Allied war effort. It all very neatly fitted the tradition and style from which it was derived. But Marrinan was also nearly contemporary with his subject; and in writing about Mayne’s postwar life, he found that it was too dull to be of interest, for he devoted only ten pages to it. However, he left two references about Mayne which were to prove prescient. He wrote that during Mayne’s lifetime, exaggerated stories about him were widely circulating; and, secondly, he did his best, according to the way society percei

ved it at the time, to encapsulate Mayne’s state of mind after the war. And there things may well have remained.

However, twenty years later the SAS attack on the Iranian embassy was filmed by television cameras and the regiment became the subject of intense public interest. A generation after Marrinan’s book appeared, Bradford and Dillon wrote about Mayne.9 They too presented him in heroic mould, but they gave their subject a more modern treatment, portraying him as a flawed hero. Not only did they accept the received version of Mayne’s entry to the SAS – via a prison cell – but with them the tale reached its apotheosis; for they postulated that it might have occurred because he was not selected to take part in what became known as the Rommel Raid, and lashed out in anger. In truth, of course, by the time the idea of an attempt to kill or capture Rommel was discussed as an option for No. 11 Commando, Mayne had been out of the unit for three and a half months. Although their treatment was modern, it had overtones of the classical tragic hero of drama who is fatally flawed. Now even assuming a punch had been thrown at a senior officer (junior officers have punched their superiors in the past and will do so in the future), it is hardly an indication of a deep character flaw. But according to Bradford and Dillon’s account, the tendency recurred throughout Mayne’s career, the evidence for which came from anecdotal accounts collected over forty years after the events. Moreover, they portrayed him as something of a serial assailant. For example, they produced a new tale that was not in circulation in Marrinan’s time, the events of which were supposed to have occurred at the end of the desert war. The plausibility of these tales is heightened by their association with a well-known figure – the son of the Director of Combined Operations, or the well-known broadcaster, Richard Dimbleby – but this is also where they fall apart, when dates and movements are analysed. Nonetheless, Bradford and Dillon’s interpretation of Mayne passed into the canon of books about the desert war and the SAS Regiment.

Paddy Mayne

Paddy Mayne